By Sheila Bair, contributor

From left: Goldman's Lloyd Blankfein, J.P. Morgan Chase's Jamie Dimon, Citigroup's Vikram Pandit, and Merrill Lynch's John Thain leaving the Treasury in October 2008 after being offered a $125 billion bailout package

FORTUNE -- Few players had as close a view of the financial crisis as Sheila Bair, chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. from June 2006 to July 2011. In this excerpt from her new book, Bull by the Horns: Fighting to Save Main Street From Wall Street and Wall Street From Itself, Bair, a Fortune columnist, describes a crucial meeting she attended at the Treasury Department on Monday, Oct. 13, 2008. There Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson persuaded a roomful of bank CEOs, including J.P. Morgan's Jamie Dimon, Citigroup's Vikram Pandit, and Goldman's Lloyd Blankfein, to go along with a $125 billion TARP bailout.

I took a deep breath and walked into the large conference room at the Treasury Department. I was apprehensive and exhausted, having spent the entire weekend in marathon meetings with Treasury and the Fed. I felt myself start to tremble, and I hugged my thick briefing binder tightly to my chest in an effort to camouflage my nervousness. Nine men stood milling around in the room, peremptorily summoned there by Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson. Collectively, they headed financial institutions representing about $9 trillion in assets, or 70% of the U.S. financial system. I would be damned if I would let them see me shaking. I nodded briefly in their direction and started to make my way to the opposite side of the large polished-mahogany table, where I and the rest of the government's representatives would take our seats, facing off against the nine financial executives once the meeting began. My effort to slide around the group and escape the need for hand shaking and chitchat was foiled as Wells Fargo (WFC) chairman Richard Kovacevich quickly moved toward me. He was eager to give me an update on his bank's acquisition of Wachovia, which, as chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC), I had helped facilitate. He said it was going well. I told him I was glad. Kovacevich could be rude and abrupt, but he and his bank were very good at managing their business and executing on deals. I had no doubt that their acquisition of Wachovia would be completed smoothly and without disruption in banking services to Wachovia's customers, including the millions of depositors the FDIC insured.

MORE: Forget Washington - here's how we'd fix the economy

As we talked, out of the corner of my eye I caught Vikram Pandit looking our way. Pandit was the CEO of Citigroup (C), which had earlier bollixed its own attempt to buy Wachovia. There was bitterness in his eyes. He and his primary regulator, Timothy Geithner, the head of the New York Federal Reserve Bank, were angry with me for refusing to object to the Wells acquisition of Wachovia, which had derailed Pandit's and Geithner's plans to let Citi buy it with financial assistance from the FDIC. I had had little choice. Wells was a much stronger, better-managed bank and could buy Wachovia without help from us. Wachovia was failing and certainly needed a merger partner to stabilize it, but Citi had its own problems -- as I was becoming increasingly aware. The last thing the FDIC needed was two mismanaged banks merging. Paulson and Bernanke did not fault my decision to acquiesce in the Wells acquisition. They understood that I was doing my job -- protecting the FDIC and the millions of depositors we insured. But Geithner just couldn't see things from my point of view. He never could.

Pandit looked nervous, and no wonder. More than any other institution represented in that room, his bank was in trouble. Frankly, I doubted that he was up to the job. He had been brought in to clean up the mess at Citi. He had gotten the job with the support of Robert Rubin, the former secretary of the Treasury who now served as Citi's titular head. I thought Pandit had been a poor choice. He was a hedge fund manager by occupation and one with a mixed record at that. He had no experience as a commercial banker, yet now he was heading one of the biggest banks in the country.

Still half-listening to Kovacevich, I let my gaze drift toward Kenneth Lewis, who stood awkwardly at the end of the big conference table, away from the rest of the group. Lewis, the head of the North Carolina-based Bank of America (BAC) -- had never really fit in with this crowd. He was viewed somewhat as a country bumpkin by the CEOs of the big New York banks, and not completely without justification. He was a decent traditional banker, but as a dealmaker his skills were clearly wanting, as demonstrated by his recent, overpriced bids to buy Countrywide Financial, a leading originator of toxic mortgages, and Merrill Lynch, a leading packager of securities based on toxic mortgages originated by Countrywide and its ilk. His bank had been healthy going into the crisis but would now be burdened by those ill-timed, overly generous acquisitions of two of the sickest financial institutions in the country.

Still half-listening to Kovacevich, I let my gaze drift toward Kenneth Lewis, who stood awkwardly at the end of the big conference table, away from the rest of the group. Lewis, the head of the North Carolina-based Bank of America (BAC) -- had never really fit in with this crowd. He was viewed somewhat as a country bumpkin by the CEOs of the big New York banks, and not completely without justification. He was a decent traditional banker, but as a dealmaker his skills were clearly wanting, as demonstrated by his recent, overpriced bids to buy Countrywide Financial, a leading originator of toxic mortgages, and Merrill Lynch, a leading packager of securities based on toxic mortgages originated by Countrywide and its ilk. His bank had been healthy going into the crisis but would now be burdened by those ill-timed, overly generous acquisitions of two of the sickest financial institutions in the country.

Other CEOs were smarter. The smartest was Jamie Dimon, the CEO of J.P. Morgan Chase (JPM), who stood at the center of the table, talking with Lloyd Blankfein, the head of Goldman Sachs (GS), and John Mack, the CEO of Morgan Stanley (MS). Dimon was a towering figure in height as well as leadership ability. He had forewarned of deteriorating conditions in the subprime market in 2006 and had taken preemptive measures to protect his bank before the crisis hit. As a consequence, while other institutions were reeling, mighty J.P. Morgan Chase had scooped up weaker institutions at bargain prices. Several months earlier, at the request of the New York Fed, and with its financial assistance, he had purchased Bear Stearns. A few weeks earlier he had purchased Washington Mutual, a failed West Coast mortgage lender, from us in a competitive process that had required no financial assistance from the government.

Blankfein and Mack listened attentively to whatever it was Dimon was saying. They headed the country's two leading investment firms, both of which were teetering on the edge. Blankfein's Goldman Sachs was in better shape than Mack's Morgan Stanley. Both suffered from high levels of leverage, giving them little room to maneuver as losses on their mortgage-related securities mounted. Blankfein, whose puckish charm and quick wit belied a reputation for tough, if not ruthless, business acumen, had recently secured additional capital from the legendary investor Warren Buffett. Buffett's investment had not only brought Goldman $5 billion of much-needed capital but had also created market confidence in the firm: If Buffett thought Goldman was a good buy, the place must be okay. Similarly, Mack, the patrician head of Morgan, had secured commitments of new capital from Mitsubishi Bank. The ability to tap into the deep pockets of this Japanese giant would probably by itself be enough to get Morgan through.

Not so Merrill Lynch, which was insolvent. Even as clear warning signs had emerged, Merrill had kept taking on more leverage while loading up on toxic mortgages. Merrill's new CEO, John Thain, stood outside the perimeter of the Dimon-Blankfein-Mack group, trying to listen in. Frankly, I was surprised that he had even been invited. He was younger and less seasoned than the rest of the group. He had been Merrill's CEO for less than a year. His main accomplishment had been to engineer its overpriced sale to Bank of America. Once the BofA acquisition was complete, he would no longer be CEO, if he survived at all. [He didn't. He was subsequently ousted over his payment of excessive bonuses and lavish office renovations.] At the other end of the table stood Robert Kelly, the CEO of Bank of New York (BK), and Ronald Logue, the CEO of State Street Corp. (STT)

MORE: The 5 myths of the great financial meltdown

The game plan for the meeting was for Hank to tell all the CEOs that they would have to accept government capital investments in their institutions, at least temporarily. Yes, it had come to that: The government of the United States, the bastion of free enterprise and private markets, was going to forcibly inject $125 billion of taxpayer money into those behemoths to make sure they all stayed afloat. Not only that, but my agency, the FDIC, had been asked to start temporarily guaranteeing their debt to make sure they had enough cash to operate, and the Fed was going to be opening up trillions of dollars' worth of special lending programs. All that, yet we still didn't have an effective plan to fix the unaffordable mortgages that were at the root of the crisis.

The room became quiet as Paulson entered, with Bernanke and Geithner in tow. We all took our seats. He got right to the point. We were in a crisis and decisive action was needed, he said. Treasury was going to use the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) to make capital investments in banks, and he wanted all of them to participate.

Paulson asked Geithner to tell each bank how much capital it would accept from Treasury. He eagerly ticked down the list: $25 billion apiece for Citigroup, Wells Fargo, and J.P. Morgan Chase; $15 billion for Bank of America; $10 billion each for Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley; $3 billion for Bank of New York; $2 billion for State Street.

Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson in a October 2008 press conference in Washington explaining the bank bailout. Behind him, from left: Fed chairman Ben Bernanke; FDIC chairman Sheila Bair; New York Fed chief Tim Geithner; Comptroller of the Currency John C. Dugan; SEC head Christopher Cox; and Office of Thrift Supervision chairman John M. Reich.

Then the questions began.

Thain, whose bank was desperate for capital, was worried about restrictions on executive compensation. I couldn't believe it. Where were the guy's priorities? Lewis said that BofA would participate and that he didn't think the group should be discussing compensation. I watched Vikram Pandit scribbling numbers on the back of an envelope. "This is cheap capital," he announced. I wondered what kind of calculations he needed to make to figure that out. Treasury was asking for only a 5% dividend. For Citi, of course, that was cheap; no private investor was likely to invest in Pandit's bank. Kovacevich complained, rightfully, that his bank didn't need $25 billion in capital. I was astonished when Hank shot back that his regulator might have something to say about whether Wells' capital was adequate if he didn't take the money. Dimon, always the grownup in the room, said that he didn't need the money but understood it was important for system stability. Blankfein and Mack echoed his sentiments.

A Treasury aide distributed a terms sheet, and Paulson asked each of the CEOs to sign it, committing their institutions to accept the TARP capital. John Mack signed on the spot; the others wanted to check with their boards, but by day's end, they had all agreed to accept the money.

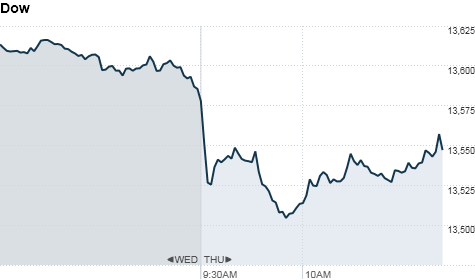

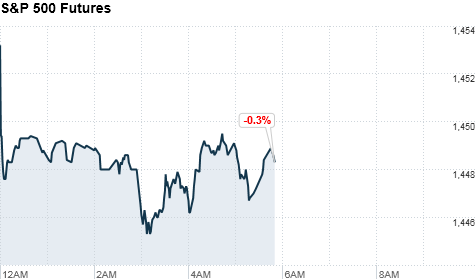

We publicly announced the stabilization measures on Tuesday morning. The stock market initially reacted badly but later rebounded. "Credit spreads" -- a measure of how expensive it is for financial institutions to borrow money -- narrowed significantly. All the banks survived; indeed, the following year their executives were paying themselves fat bonuses again.

In retrospect, the mammoth assistance to those big institutions seemed like overkill. I never saw a good analysis to back it up. But that was a big part of the problem: lack of information. When you are in a crisis, you err on the side of doing more, because if you come up short, the consequences can be disastrous.

MORE: Surprise! The Big Bad Bailout Is Paying Off

The fact remained that with the exception of Citi, the commercial banks' capital levels seemed to be adequate. The investment banks were in trouble, but Merrill had arranged to sell itself to BofA, and Goldman and Morgan had been able to raise new capital from private sources, with the capacity, I believed, to raise more if necessary. Without government aid, some of them might have had to forgo bonuses and take losses for several quarters, but still, it seemed to me that they were strong enough to bumble through. Citi probably did need that kind of massive government assistance (indeed, it would need two more bailouts later on), but there was the rub. How much of the decision-making was being driven through the prism of the special needs of that one, politically connected institution? Were we throwing trillions of dollars at all the banks to camouflage its problems? Were the others really in danger of failing? Or were we just softening the damage to their bottom lines through cheap capital and debt guarantees?

Granted, in late 2008 we were dealing with a crisis and lacked complete information. But throughout 2009, even after the financial system stabilized, we continued generous bailout policies instead of imposing discipline on profligate financial institutions by firing their managers and boards and forcing them to sell their bad assets.

The system did not fall apart, so at least we were successful in that, but at what cost? We used up resources and political capital that could have been spent on other programs to help more Main Street Americans. And then there was the horrible reputational damage to the financial industry itself. It worked, but could it have been handled differently? That is the question that plagues me to this day.

This story is from the October 8, 2012 issue of Fortune.

Excerpted from Bull by the Horns: Fighting to Save Main Street From Wall Street and Wall Street From Itself, by Sheila Bair. Copyright © 2012 by Sheila Bair. To be published September 25, 2012, by Free Press, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

20 Sep, 2012

-

Source:

http://rss.cnn.com/~r/rss/money_topstories/~3/Wd-gvGd-3NE/--

Manage subscription | Powered by

rssforward.com

FORTUNE -- On the face of it, Hewlett-Packard and IBM have a lot in common. Both are storied brands with rich legacies that shaped high-tech. Both are working with companies large and small to help manage their technology. Both are angling for a piece of the markets -- like cloud computing and big data -- that promise years of growth.

FORTUNE -- On the face of it, Hewlett-Packard and IBM have a lot in common. Both are storied brands with rich legacies that shaped high-tech. Both are working with companies large and small to help manage their technology. Both are angling for a piece of the markets -- like cloud computing and big data -- that promise years of growth.

FORTUNE -- The sixth major update of Apple's (AAPL) mobile operating system is old news to the developers and tech writers who've been playing with it all summer. But the formal reviews of iOS 6 only began to appear on Wednesday, when the software became available for download to the other several hundred million owners of Apple mobile devices.

FORTUNE -- The sixth major update of Apple's (AAPL) mobile operating system is old news to the developers and tech writers who've been playing with it all summer. But the formal reviews of iOS 6 only began to appear on Wednesday, when the software became available for download to the other several hundred million owners of Apple mobile devices.

Still half-listening to Kovacevich, I let my gaze drift toward Kenneth Lewis, who stood awkwardly at the end of the big conference table, away from the rest of the group. Lewis, the head of the North Carolina-based Bank of America (BAC) -- had never really fit in with this crowd. He was viewed somewhat as a country bumpkin by the CEOs of the big New York banks, and not completely without justification. He was a decent traditional banker, but as a dealmaker his skills were clearly wanting, as demonstrated by his recent, overpriced bids to buy Countrywide Financial, a leading originator of toxic mortgages, and Merrill Lynch, a leading packager of securities based on toxic mortgages originated by Countrywide and its ilk. His bank had been healthy going into the crisis but would now be burdened by those ill-timed, overly generous acquisitions of two of the sickest financial institutions in the country.

Still half-listening to Kovacevich, I let my gaze drift toward Kenneth Lewis, who stood awkwardly at the end of the big conference table, away from the rest of the group. Lewis, the head of the North Carolina-based Bank of America (BAC) -- had never really fit in with this crowd. He was viewed somewhat as a country bumpkin by the CEOs of the big New York banks, and not completely without justification. He was a decent traditional banker, but as a dealmaker his skills were clearly wanting, as demonstrated by his recent, overpriced bids to buy Countrywide Financial, a leading originator of toxic mortgages, and Merrill Lynch, a leading packager of securities based on toxic mortgages originated by Countrywide and its ilk. His bank had been healthy going into the crisis but would now be burdened by those ill-timed, overly generous acquisitions of two of the sickest financial institutions in the country.